Issue : 1 Article : 1

Uncultivated Edible Greens (UCG) - A Less Explored Aspect of Contribution of Small Millet Cropping Systems (SMCS) for Nutrition of Poor Rural Families in India

Karthikeyan. M, Principal Investigator-India, Revalorising Small Millets in Rainfed Regions of South Asia (RESMISA) Project, DHAN Foundation, India,

karthikeyanrfd@gmail.com

Salome Yesudas, Freelance consultant Sathya, Project staff

Introduction

Food and nutritional security continues to be a daily challenge for about one billion people around the world. India too is reeling under serious nutrition issues with around half of the pre-school children suffering from undernutrition. Micronutrient deficiencies are also widespread with more than half the women and children suffering from anaemia and suboptimal reduction in Vitamin-A deficiency and iodine deficiency disorders (IDD) (Government of India). This is in spite of the significant growth of the economy in the recent past, increase in food production and provision of food through public distribution system (PDS) and other supplementary food programmes. There is urgency to address these food and nutrition security issues through additional ways. One such avenue that has the potential to address the nutritional insecurity issues is increased utilization of neglected and underutilized species (NUS). Small millets are an important part of NUS and they offer better nutrition than commonly consumed rice and wheat, in terms of various micronutrients (vitamin B, calcium, iron and sulphur), high dietary fibre and low glycemic index. Small millets are valued for their preventive and curative health properties (Varma & Patel, 2013; Yenagi and Mannurmath, 2013). They are also known for their water stress tolerance, which makes them suitable for rainfed agricultural systems threatened by climate change. Small millet cropping systems (SMCS) offer food security, fodder security and income security to the cultivating households. Besides these advantages, small millet farms accommodate many nutritious uncultivated greens. Not much focus is given for understanding the contribution of uncultivated greens in the small millet farms to the food and nutrition security at the community level and for strengthening the same.

A study on uncultivated greens in association with small millets was taken up in three sites lying in different agro-climatic regions of Tamil Nadu, India, as UCGs are integral part of the SMCS. The study was carried out with the objectives of documenting UCGs from the project sites with the focus on those from in and around small millet farms, documenting recipes of uncultivated greens, understanding the trend in consumption of uncultivated greens and understanding knowledge transmission related to UCG across generations. The methods followed, and the results and insights from the study are as follows.

Methodology

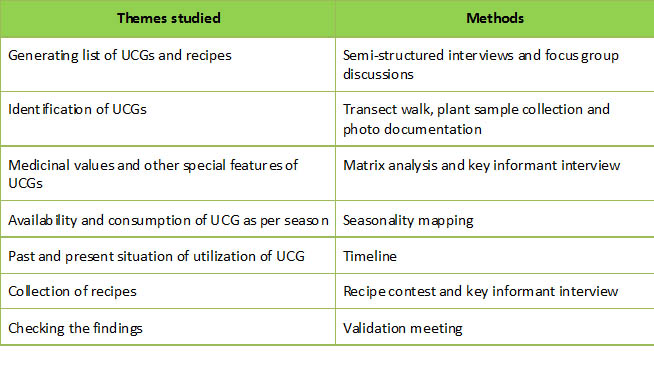

The word “uncultivated” is used in a more general way to denote any of the following three categories: (1) greens from land that are not cultivated such as plant, creeper, etc.; (2) greens that are not cultivated but are available as per partner crop in a cultivated field; and (3) greens that are available from cultivated plants, but the product was not the explicit objective of the cultivation (Suresh Reddy & Salome, 1998). Participatory methods were used to understand the whole scenario of UCG in local food systems (see Table 1). To generate UCGs list and the list of recipes being in use, interviews of respondents using semi-structured questionnaire and focus group discussions were held with farmers of different age and gender. For semi-structured interviews, various age groups namely 20–30, 31–40, 41–50 and above 51 years were considered. Gender and age variations were selected purposefully to obtain diverse knowledge from a cross-section of the population. Identification of UCGs was done through transect walk and systematic collection of plant sample was also carried to prepare a herbarium of all edible UCGs besides photo documentation. Matrix analysis and seasonality study were conducted to obtain the community perception on medicinal values, other special features of uncultivated greens and the months in which the UCGs are available. Timeline and trend analysis of utilization of UCGs was also done. Formal and informal talks helped much to document the merits of UCGs perceived by the local community. During repeated visits to the study site, further key informant interviews were held with aged persons and with women, who were skilled in the use of uncultivated greens. Recipe contest was conducted for documenting the rich knowledge of women on recipes of UCGs and their utilization. In the end of the study, validation of results was done by sharing the study results with the groups of local community members and the results were accordingly refined. From the existing data sources, the botanical name and nutrient composition of UCGs was sourced and documented. The botanical names were confirmed with the help of taxonomists.

Table1 : Details of methods used in the study

Location of the study

Matrix analysis in progress in Anchetty |

The field research was conducted in RESMISA project sites, Jawadhu hills (Tiruvannamalai district), Anchetty (Krishnagiri district) and Peraiyur (Madurai district) in Tamil Nadu state of India. Jawadhu Hills is a remote hilly site with tribal farmers. It is characterised by red loamy soil, high rainfall, small land holding size and limited adoption of technologies. Little and finger millets are the main small millet crops here. Anchetty site is located in the Karnataka border and occupied by non-tribal farmers. It is characterised by undulating land with red loamy soil, low rainfall, moderate land holding size and high adoption of technologies. Finger millet is the focus small millet crop here. In both these locations, the villages are surrounded by forests. Peraiyur site is different from the other two sites in various ways. It is a well-connected site with non-tribal farmers. It is characterised by plain land with black soil, low rainfall, moderate land holding size and limited adoption of technologies. Barnyard and kodo millets are the focus small millet crops here. So the study attempted to analyse the UCGs in three different agro-climatic regions in Tamil Nadu with different kind of local communities. The UCGs were documented in five panchayats (Thagatti, Urigam, Kottaiyur, Madakkal and Anchetty) covering 26 villages in Anchetty, four panchayats (Kovilur, Kuttakarai, Melsilambadi and Nammiyampattu) covering 41 villages in Jawadhu hills and 13 villages in Peraiyur. The study was taken up during the rainy season during which the UCGs were available in plenty. |

Interview in progress |

Results and discussion

Presence and availability

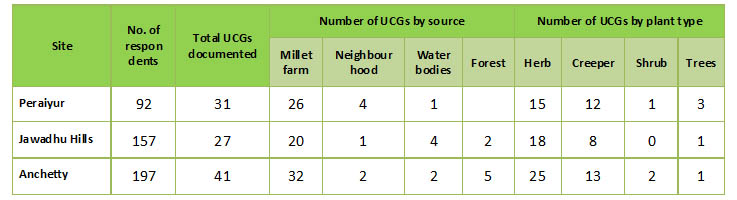

As shown in Table 2, considerable number of UCGs was documented in the sites and majority of them (about 75%) were sourced from small millet farms. Source of UCGs also reflect the agro-ecological condition of the sites – presence of forests in Anchetty and Jawadhu Hills. Majority of the UCGs belong to herb and creeper plant type. Considerably more number of UCGs was documented in Anchetty when compared to other two sites.

Uncultivated greens are actually weeds that grow in millet farms and some of them are considered more menacing than others as they reduce yield. Every rainy season, they grow on their own along with the crops and are available for 3–4 months starting from late June to December in the case of Anchetty and Jawadhu Hills, and September to November in Peraiyur. Seenga keerai is available in May to April and October to November period and the people consume its tender leaves only. Manathakkali and Ponnanganni are available throughout the year. Besides the farm, many UCGs, including some thorny plants, also grow on hedges. In most of the UCGs, the edible part is the leaf and stems; in some cases, fruits (e.g. Manathakkali and Kara) and roots (e.g. Nerinji) are also edible. The names of some of the UCGs vary across the sites. UCGs are accessible to all the families in the local area, including the landless.

Table 2: Uncultivated greens documented in the sites – source and plant type

UCG recipes in vogue

|

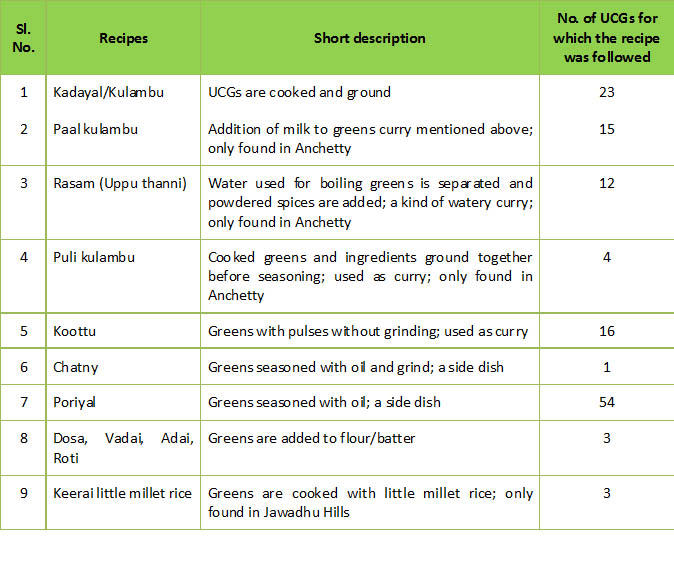

Uncultivated greens are cooked in simple ways, involving less work. The study found that nine kinds of recipes are in practice (see Table 3). Some of the recipes are location-specific and others are common across the sites. Cooking with milk and tamarind and consuming as soup was observed only in Anchetty. In Anchetty, common recipes are pal kulambu, kulambu and poriyal. Rare recipes are dhosa and roti, in which UCGs are used as ingredient. In Jawadhu hills, common recipes are kulampu and poriyal, and rare recipes are dhosa, roti and little millet keera rice. In Peraiyur, common recipes are kulampu, kootu and poriyal, and rare recipes are vada, adai, chatny, poriyal with blood of goat and dhosa. The UCG recipes go well with small millet main dish. Muddhe (boiled finger millet flour made into balls), roti (finger millet handmade rotis baked on pan), cooked rice, porridge or whatever may be the cooked form of the millet, the UCGs are good accompaniments in terms of taste and nutrition. In Anchetty, finger millet being the staple crop, UCGs are regularly eaten with finger millet recipes such as muddhe. In other two sites, the situation is different as the staple crop is rice. |

Recipe contest in Jawadhu Hills |

Table 3: Uncultivated greens’ recipes documented in the sites

Perception of health benefits

Community members’ perception on various health attributes of UCGs was also documented in the study and few of them are shared here. It was reported in Jawadhu Hills that Pannai keerai (Celosia argentea) Kanan (Commelina benghalensis), Sadakuppi (Aurthum graveolus wild), Ponnanganni (Alternanthera sessilis), Manathakkali keerai (Solanum nigrum), Thavarai keerai (Cassia tora), Thoyya keerai (Digera arvensis), are cold foods (producing cooling effect) and Seenga keerai is a hot food (heat producing). So, Seenga keerai (Acacia pennata) is not consumed by pregnant ladies. Thoyya keerai and Ponnaganni keerai are considered good for lactating women. Perandai (Vitis quadrangularis) is considered good for digestion. Ponnanganni keerai is considered good for eyesight, skin and cooling the body. Manathakkali is considered good for healing stomach ulcer. The excess consumption of Seenga keerai causes joint pain and gastric problem. Local traditional healers use UCGs in their medicinal preparations.

Consumption of UCGs

Intensity of consumption varies from season to season, with more consumption during rainy season (2 to 4 days in a week) due to easy availability. The most favoured UCGs include Pannai, Thoyya, Manathakkali, Ponnanganni, Mullu, Thiruvannamalai and Neermulli. Though considerable consumption of UCGs was observed in the three sites, declining trend was reported when compared to the earlier years. The reasons for decline in consumption varied across the locations. Consumption of UCGs from forest has come down in Anchetty due to less access. On the other hand, consumption has come down in Peraiyur due to reduction in availability of UCGs from farms and decline in cultivation of small millets. In the case of Jawadhu Hills, consumption of UCGs is being replaced by purchased vegetables and this trend is seen as a sign of social mobility – increase in social status. It was reported that children have less preference for UCG recipes.

Influence of age and gender on knowledge of UCGs

Knowledge about these UCGs is handed over from one generation to another as an oral tradition. Their food, nutrition and medicinal values were carefully handed over by observation. As the young, especially women, accompany elders for weeding, they learn about the collection of these weeds for different uses, some for food, some for medicine and some as medicine for their animals. They also learn about recipes and various related nuances from their elders. The study revealed that in Anchetty, there is considerable difference in knowledge on UCGs between men and women with, women knowing (7.85 on an average) more UCGs than men (6.73). Similarly, there is difference in knowledge on UCGs among the different age groups with “above 51 years” age group knowing more than their youngsters. In Jawadhu Hills, these differences were not well-expressed. Both in terms of gender and age group, there was no significant difference. This indicates the decline in transmission of knowledge across the generations in Anchetty and less evidence of such trend in Jawadhu Hills. On the other hand, more number of UCGs was reported by an individual respondent in Anchetty, than in Jawadhu Hills. The maximum and minimum number of UCGs reported by respondents was 22 and 3 in Anchetty and 14 and 2 in Jawadhu Hills.

Comparison of UCGs with cultivated greens

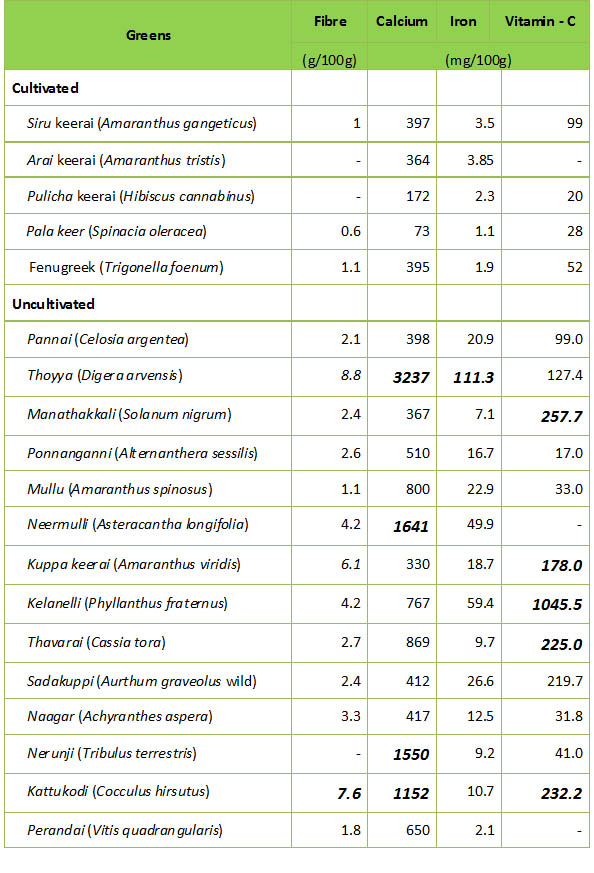

A comparison of nutritional profiles of the UCGs with cultivated and commonly consumed greens (Table 4) revealed that UCGs fare better as they have much higher value of nutrients, especially micronutrients. So, they are good candidates for improving the nutritional security of local community.

Table 4: Comparison of nutritional profile of UCGs with commonly consumed cultivated greens

Source: 1) APFAMGS & FAO (2007), Nourishing Traditions: Local Greens. 2) Gopalan, C., Rama Sastri, B.V., Balasubramanian, S.C., Narasinga Rao, B.S., Deosthala, Y.G. & Pant, K.C. (2007), Nutritive values of Indian Foods, National Institute of Nutrition, Indian Council of Medical Research, Hyderabad.

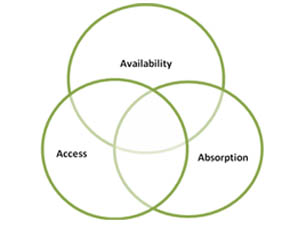

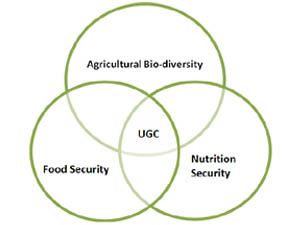

ConclusionThe three aspects that underlie most conceptualizations of food and nutrition insecurity are (1) Availability – the physical availability of food stocks in desired quantities; (2) Access – determined by the bundle of entitlements, especially in terms of physical and economic access to food; and (3) Absorption – defined as the ability to biologically utilize the food consumed (MSSRF & WFP, 2008). UCGs are rich sources of iron and vitamin C and both play a vital role in red blood cell formation. They are also rich in calcium and phosphorus, other important twin micronutrients that help in bone and teeth formation and also for many other important biological functions in the body. These UCGs offer fibre in plenty which is missing in modern diet. Fibre is a very important element for preventing constipation and certain types of cancers. Uncultivated greens as part of the local food systems are available in plenty and accessible relatively free of cost to all the members of the community, including the landless. It was reported by women respondents that whenever they need, they just walk to the nearby field and hand pick their choice of UCGs and cook them as they want. Due to their richness in vitamins and minerals, the UCGs help in absorption of nutrients from the accompanying energy-giving bulk foods, whether it is rice, finger millet or other small millets. Thereby, UCGs serve as a solution for various micronutrient issues plaguing all classes of society in the sites. So, they lie at the intersection of three dimensions of food and nutrition security (see Figure 1). As being part of agricultural biodiversity and by their role in food and nutrition security, they again lie at the intersection between agricultural biodiversity, food security and nutrition security. In summary, SMCSs in addition to their produce provide many valuable UCGs to the site community. UCGs are freely available to all the local community members and are rich source of vitamins and minerals and play a pivotal role in meeting the micronutrient requirements of the rural families in the sites. Moreover, they contribute to better absorption of rich nutrients available in the small millets by the body. Given these benefits of UCGs, it is important to conserve and nurture them. Specific efforts are also needed to counteract the declining trend in UCG consumption by taking proactive steps to facilitate transmission of knowledge about UCGs to children and youngsters. Initiatives such as recipe demonstration and educating school children through various communication tools are needed. Sustenance of UCGs in the future is very much linked to the sustenance of rainfed farming ecosystem in general and small millet farming in specific, since these UCGs come mainly from small millet farms and small millet cultivation is the base for their existence. This is another reinforcing reason for supporting the rainfed farming livelihoods and small millet cultivation. Further research is needed on nutritional composition of some of the UCGs for which data is not available from secondary sources and bioavailability of combination of small millets and UCG foods. |

Figure 1: Role of UCGs in food and nutrition security

|

References:

1. Government of India, Report of the Steering Committee of Nutrition, Planning Commission, New Delhi.

http://planningcommission.nic.in/aboutus/committee/strgrp/stgp_nutri.pdf

2. MSSRF and WFP (2008), Report on the state of food insecurity in rural India.

3. Suresh Reddy B & Salome Yesudas B. (1998). Uncultivated greens; Major source of food for the poor in the Zaheerabad region of Deccan, India, DDS.

4. Varma, V. and Patel S. (2013), Value Added Products From Nutri-Cereals: Finger Millet (Eleusine coracana). Emirate Journal of Food and Agriculture, 25(3): 169-76.

5. Yenagi, N. and Mannurmath, M. (2013), Millets for Food and Nutritional Security: Lead Paper. National Seminar on Recent Advances in Processing, Utilisation and Nutritional Impact of Small Millets, Madurai, India. TNAU and DHAN Foundation, India.